September 21, 1846

In November, 1812, the left wing of the Army of the Northwest, commanded by General Winchester, was stationed at a camp on the Maumee River six miles below Fort Defiance at the mouth of the Augaize and about forty-five miles above the rapids. The Kentucky volunteers had served more than half of their term and were becoming restless because of inaction and starvation; they were very anxious to go out in quest of food and fighting. On November 21 General Payne had intimated to Logan a doubt concerning the latter's fidelity to the American cause, since Logan's uncle was commanding the Indians allied with the British. This suspicion was rather roughly expressed, and it fired the noble Indian to a degree of excitement; he avowed his fixed resolution to give unmistakable evidence of his honor and courage. A large force of the enemy had located itself at the rapids, and Logan determined to go there and take a prisoner or lose his scalp in the effort.

I was then a beardless cabet only eighteen years old. By order of General Payne, I had been attached to Colonel Charles Scott's regiment of Kentucky volunteers. On that day I was detained for guard duty as a subaltern officer in command of twenty-four men. My position was near the river below the camp, and my line of sentinels extended out at right angles for two or three hundred yards in order to protect the flank of the army. Although it was cold, the day was bright and beautiful and the air was crisp. At early dawn, as the last notes of the reveille echoed through the air, Logan was conducted by the officers of the day through the outer lines of the army. On his perilous enterprise, he was accompanied only by two Shawee warriors from Wapakoneta, his own village. The first, Captain Johnny, was a tall, swarthy, villainous-looking fellow. He was not popular with the troops because they believed he had fought against General Harrison at the battle of Tippecanoe. The other was a noble-looking young Indian about twenty-two years of age who was known by the English name of Bright-horn. Subsequently, he distinguished himself in Dudley's defeat while under my immediate command. The boldness and the extremely hazardous nature of this voluntary undertaking excited our highest admiration, but many of us expressed serious apprehensions concerning the consequences to the daring chief and his intrepid companions.

Military men know that the officer in command of a camp guard never sleeps while on duty. Consequently, midnight found me awake. Lying on my back with my head to the light, I was reading one of Miss Porter's novels; my men wrapped in their blankets, were sleeping around the fire. The night was clear and dark, and all was silent and quickly repeated challenges of one ot the sentinels neasrest the river bank. As I sprang to my feet to arouse the guard, I recognized Logan's voice. Answering the challenge and announcing himself, he said, "My friends, we have had a bloody battle, I am badly wounded," I was greatly shocked by this reply. All day long I had been talking and thinking of him. Instead of his usually loud, musical, and manly voice, I heard his feeble and tremulous answer, and I did not wait for any military formula. Immediately, I ordered the sentinel to let him pass, and I hastened him and conduct him to the fire. He was accompanied only by Brighthorn, and both of them were well mounted. I knew they had left camp that morning on foot, as there was only one horse in that wing of the army. All of the other horses had perished or been sent into the interior.

At my request, Logan immediately proceeded to give me an account of the events of the day. He and his companions had left the beaten path along the riverbank and had taken a low swamp route a mile or two away in order to avoid observation or discovery. Before they had gone ten miles, however, they saw six persons on horseback short distance ahead. These six were traveling the same presumably safe and secret way but were coming from opposite direction.

It required no interpreter to inform Logan and his companions that they were within rifle shot of six deadly enemies. It was to late to think of flight through the open woods in daylight with any hope of escape; and it would be madness to fight while outnumbered two to one. But the steady, poised chief did not hesitate in the adoption of his plan, and his promptness of action probably saved him from immediate death. His companions watched his countenance and all his movements with keen concern. They were ready to second or sanction whatever he might do or say. Logan resolved to attempt by stratagem what he despaired of effecting by immediate combat. He did not halt in his onward march and manifested neither surprise nor alarm, but with a bland smile he hastened to meet and salute the horsemen. Indeed, he expressed his high gratification at the unexpected good fortune of finding them so near at hand. Now he need not go all the way to the rapids to see them and communicate the important intelligence which he possessed. Skillfully blending fact and falsehood to give a semblance of truth to all he said, he told them that an early movement of Winchester's army was contemplated.

If anything could have shaken Logan's firm nerves or caused him to hesitate a moment, it would have been a fact which he discovered only after coming in close contact with the strangers. Their leader was his deadly personal foe--an Indian celebrated for his cunning, courage, and cruelty-- Winamac, the great Potawatomi chief. Among the others was Captain Elliott, a half-breed son of Colonel Elliott of the British army. The latter was well known afterward for his cold-blooded treachery to the unfortunate Kentucky captives taken at the Raisin and Dudley's defeat. A tall, young Ottawa chief and three grim-looking, painted warriors were also in the group.

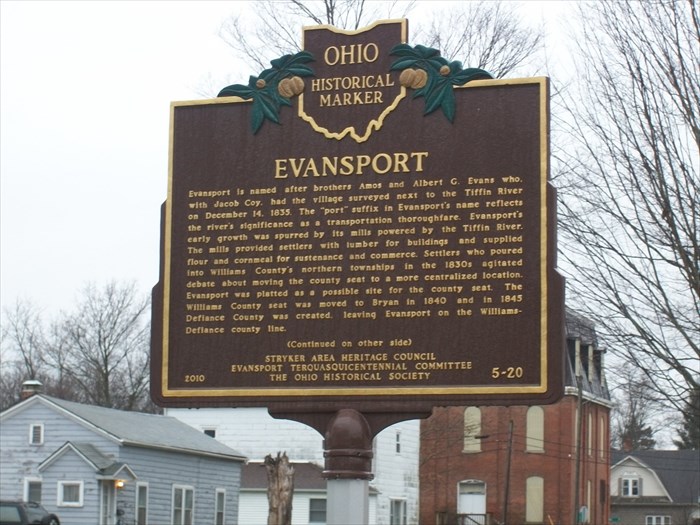

Immediately at the outbreak of the war,the British government had taken measures to enlist under the immediate control of Colonel Elliott all the tribes of Canada. Those tribes,.led by Robert Dixon and Tecumseh, on the northern and western frontiers of the United States also joined the British cause. Tecumseh was the prime mover of the hostile operation of the Indians against us. After Hull's surrender at Detroit, a large body of these Indians had moved forward to attack Fort Wayne. They had been driven back by General Harrison and were encamped at the rapids of the Maumee River nearly opposite the point where Fort Meigs was afterward built. General Proctor naturally wanted to know whether General Harrison had taken up winter quarters at the points then occupied by several of the Army of the Northwest or whether he intended to invade Canada during the winter. Therefore, Proctor had dispatched this carefully selected band of six Indians to spy on Winchester's camp. If they could not secure a prisoner, they were to ascertain the intentions of the American general from preparation and appearance. Therefore, the capture of Logan was a godsend far beyond their most sanguine hopes and expectations. Logan, who had been employed for months by General Harrison as a spy and guide, would necessarily know more about the General's plans and intentions than anyone else.

The band proceeded no farther toward our camp but turned back toward the rapids. Winamc did not believe Logan's story was disposed to disarm the three Indians and to tie their hands behind them in order to avoid all possibility of danger or escape. But Captain Elliott and the others objected; they believe that there was no risk during the daytime while they were mounted and Logan and his companions were on foot. In the course of the day, Winamac asked Logan why he was now coming to join them; in the past he had always positively refused. Winamac charged that Logan had even risked his life in passing through enemy lines at the siege of Fort Wayne to urge the garrison to hold out until General Harrison's forces arrived. Logan's answer to the charge was as prompt as it was plausible. He said his family was at Wapakoneta within the American lines, and he feared that they would either be forced into settlement or be killed if he joined the British as Tecumseh had urged him to do. He also stated that General Payne's treatment of him had been so outrageous that he had determined to sacrifice everything in order to be revenged. Although he was temporarily treated as a friend, Logan saw and felt that he was distrusted by Winamac and his companions, and he realized that at night he and his comrades would be confined as prisoners.

In the evening they stopped to encamp near a small watercourse. Winamac and his party dismounted and began to unsaddle their horses. The critical moment had arrived.Not a word had passed between Logan and his fellow prisoners, but he knew their bravery and devotion and did not doubt their active and efficient co-operation in anything he might attempt. He pretended to see a squirrel in a tree short distance away and mentioned it to Captain Johnny and Brighthorn. Not a word of his bloody purpose passed his lips; he only asked them if they desired some tobacco.Then with a significant look, he handed each a leaden bullet., which they put into their mouths. In an instant, the sharp, simultaneous cracking of three rifles announced that the work of death had commenced. The quiet of the November sunset was changed into the noise of savage strife and battle.

Winamac and Captain Elliott fell dead, and one of the warriors was wounded. The combatant were thus reduced to numerical equality, but there were six loaded rifles on one side to three empty ones the other. In this emergency, Logan and his companions boldly attempted to seize the enemies' arms which had been placed against a tree. But this action was anticipated by their foes, who were fully aware of the life-or-death nature of the combat. As all rushed toward the loaded guns, the opposing parties were brought face to face. Logan's enemies jumped behind trees for shelter with their loaded rifles. A typical Indian fight began and continued until darkness ended it. Many shots were fired from Logan's rifle struck down the Ottawa chief. Brighthorn disposed of a another warrior and was severely wounded himself. attempted to move nearer the enemy. Unfortunately, at that instant, the enemy planted a ball in his body just below the center of the breastbone. The ball passed through his body and lodged just beneath the skin near the lower part of his back. Although mortally wounded, Logan did not fall. The enemy fled. Logan's last act was to drive his tomahawk into Winamac's head, That duty was left for Captain Johnny, after he had aided Logan and Brighthorn to mount the enemies' horses and start back to our camp.

Next morning the fatal ball was extracted from Logan's back without difficulty, but he was a dying man. He suffered the most acute agony without a groan and calmly provided for his wife and children. About forty-eight hours after he had received his wound, he died. When it was announced that the great chief was dead, a deep gloom settled over the army, as if a dire calamity had befallen each individual officer and soldier.

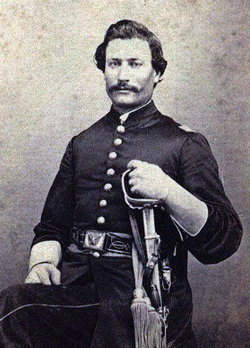

At the time of his death, Logan could not have been over forty years of age; perhaps he was not over thirty-five. He was above medium height and heavier than most Indians. He had a deep, broad chest and a high forehead. His countenance was mild, amiable, and playful rather than stern; yet it combined marked firmness and decision of character.

Please excuse any inaccuracies of style and manner. My next letter will contain a brief account of Captain Johnny's fate, Logan's funeral, and the announcement of the chief's death to his village, and the fate of Logan's family.

Yours truly

General Leslie Combs

Daily Indiana Journal, December 4,1852

September 25, 1846

My dear Sir

In my last letter I related that Captain Johnny was left on the battlefield where Logan had received hs death-wound. Captain Johnny was to scalp his dead enemies according to the customs of the savages. Logan told me that I need not expect Captain Johnny before daylight. Johnny spoke English very poorly, and he would fear being shot as an enemy if he approached the sentinels during the night. I cautioned the guards and order them to keep a sharp lookout for him.

At daybreak we were somewhat uneasy, since Captain Johnny had not made his appearance. Soon I heard a most unearthly noise near the river. It seemed to imitate the human voice, and I supposed that the Shawnee brave was trying to halloo like a white man and hail the sentinel nearest him. After advancing fifty yards toward the river, I saw the black ugly, painted face of Captain Johnny anxiously peering from behind a huge oak tree. He was repeating with all his might the strange, discordant sounds which had first attracted my attention.

I had expected him to appear on horseback with the captured steeds of the defeated foe in his train and their gory scalps at his girdle. I was much surprised to see him on foot, more haggard than usual, with only one reeking trophy of victory dangling from his belt. I hailed him and told him to comeup without fear. I was anxious to hear what had happened to him after Logan had left him. He did not need a second invitation but immediately strode toward me. He looked as proud as Lucifer. When he was about ten or fifteen paces from me, he exhibited his only evidence of success. Raising the trophy with its gory, disarrayed locks, he exclaimed exultantly, "Winamac scalp! Winamac scalp!" Latter, when Logan saw it, he declared that it was not from the head of the Potawatomi chief. Winamac had only a single tuft of long hair; this scalp was covered with long hair. At that time I was unaccustomed to sight and scenes of blood and carnage. As I looked for the first time on this horrid, savage trophy, a cold chill passed my heart.

I could understand little of his barbarous English, but it seemed that Captain Johnny had lost no time after his two companions had left him. He had torn the scalp from the skull of the warrior nearest him and was in the act of scalping when he saw a flash of light a few steps ahead. He heard the loud, ringing crack of a rifle and the same instant felt the burning of a bullet as it grazed the skin of his own head. He leaped into the air and broke his knife. Immediately, he hastened to the spot where the horses were hitched. Alarmed by his sudden, noisy approach, the animals broke loose as he came near them, and he was compelled to escape on foot from this new attack.

Captain Johnny supposed that the warrior who had fled after the shooting Logan had returned. The gathering darkness and the dense forest enabled the wily foe to creep upon him unperceived. It is probable that the departure of Logan and Brighthorn had been observed; because Captain Johnny was left behind, it was inferred that he was too badly hurt to get away. His scalp would, in some degree, compensate for the heavy loss sustained in the combat.The only survivor of the party had cautiously returned and found scalping the fallen warriors. To drive a ball through his brain was a natural instinct; the darkness saved Captain Johnny. It was well for Captain Johnny's fame that he had escaped, for previously he had been distrusted. Many would have believed that he had deserted us and again joined his old friends. But Logan said that we need never fear his fidelity again. He had shed their blood and knew he would not be spared if ever he should fall into their hands.

Before I write of Logan's funeral, you may be interested in knowing something of his birth, parentage, and early history. From reliable sources I learn that he was half-white and half-Indian. His complexion and features indicated that he was a half-breed. His father was a young man from Greenbriar County, Virginia. A great hunter in his day, he developed a disgust for quiet, inactive, unexciting, civilized life. He wandered off into the trackless forest north of the Ohio River. He settled among the Shawnee Indians and assumed their habits. His skill in the chase and his bold daring in war soon brought him into prominence; he was adopted into the tribe and later became a chief. He made the acquaintance of an Indian maiden of high birth --the elder sister of Tecumseh and the Prophet; the couple was united in marriage according to the formalities of her nation. Logan was the younger of their two sons; the elder died in childhood. By the fortunes of war, the younger boy was taken prisoner by Colonel Logan of Kentucky, who brought him home and treated him as a son. He learned to speak English fluently. After the peace treaty which followed Wayne's great victory at the rapids (Fallen Timbers), he was restore to his family and friends. In gratitude to his generous captor, he assumed the name of Logan.

While he was still a captive, all his boyish sympathies were for a little Indian girl who was also a prisoner; she had been captured about the same time and was then the cherished member of a neighboring family-- that of Colonel Hardin. Both prisoners were released at the same time. When they grew up, they were married in their native village. Major Harden, a son of Colonel Harden, was at Logan's deathbed. He tended the Indian like a brother and closed the unseeing eyes when the last struggle was over. To this gentleman, Logan entrusted the fate of his family and asked that his wife and children be moved to Kentucky, until the war had ended. "I have killed a great chief," said he, "and when I am in the land of the spirits, his friends will creep upon little ones and murder them all."

About ten o'clock on the cold, bleak morning of November 26, 1812, the fife and the solemn, muffled drum announced a military funeral. The ground was already covered with several inches of snow, and snow continued to fall. A crowd of officers and soldiers were assembled around the tent where the departed warrior lay He had been wrapped in his blanket and placed in a rude coffin made of the best materials we could obtain. Although there was little pomp and circumstance, all showed their respect for their loved and distinguished comrade.

The chaplain, the Venerable Mr. Shannon, was present. He humbly besought the Heavenly Father to have mercy on this noble son of the forest and, as but little light had been granted him on earth, to ask but little of him on the Last Day. An armed military guard of honor was also ordered on duty. After the services had been concluded, the lid of the coffin, which had been removed to allow us to look for the last time upon the noble countenance of the dead chief, was replaced and fastened down. Since we had no horses in camp, we constructed a small sled. Using thongs of rawhide for traces, the officers who acted as pallbearers hauled the body six miles to old Fort Defiance. There he was buried. A rude stone was placed at his head and another at his feet; the initials of his name were roughly carved upon the to mark the spot.

A few days afterwards Major Hardin, accompanied by Captain Johnny and one or two other officers, started on his mission to Wapakoneta. some sixty or eighty miles distant. He was charged by the commanding general to tell Logan's people the circumstances of the great chief's last battle and death and the honor paid to his memory. Harden was also to express the deep sympathy of the whole army for the chief's untimely end. Harden conferred with the chiefs and the widow concerning the removal of Logan's family to Kentucky. The proposal was respectfully decined, and Major Hardin returned to camp.

The years passed. One day I received a message saying that a company of Indians at the hotel said they knew me and desired to see me. Hoping to fine some of my campaign companions among them, I immediately called on them. I was then a bearded man and doubted that they would recognize me, even if they had formerly known me in uniform. But I had hardly entered the room when, after a moment's piercing scrutiny, one of the Indians rushed across the floor and seized me my the hand. It was my old friend Brighthorn. "Different time this," said he, "from when I last saw you."

"Yes," I replied, "for it was just before we were taken prisoners together in Dudley's defeat. We both were be grimed with the smoke of battle, and there were a few fresh scalps at your belt."

"And you," he rejoined. "were very sick, " pointing to the place an enemy's ball had penetrated my shoulder.

With the party was a tall, handsome youth, straight as an arrow, and about fourteen or fifteen years of age. He was Logan's eldest son, who had visited Kentucky with some of his father's friends and relatives. He was to decide for himself whether he would remain or not. He said he could not stay, because his heart yearned for the playmates of his childhood and the wild woods surrounding his native village. After remaining only a few days, the Indians left.

Your friend and most obedient servant,

General Leslie Combs

Daily Indiana Journal, December 8, 1852

Don Miller who was born March 30,1902, to Annie (O'Reilly) and Martin E. Miller of Defiance, lived at 18675 Parkland Drive, Shaker Heights .

Don Miller who was born March 30,1902, to Annie (O'Reilly) and Martin E. Miller of Defiance, lived at 18675 Parkland Drive, Shaker Heights .